I got an email from a friend last night. I will identify them as “they” and not locate them anywhere except within the lower 48 United States, but I will say that they are an adjunct faculty member at a couple of colleges. That’ll narrow it down to maybe a million people, so I think we’re safe.

They teach at one college that has returned to in-person instruction.

That college has started a vaccine administration system on its campus.

Adjuncts are not offered vaccination.

60% of their teaching force are adjuncts.

I mean, just from a public health standpoint, this is brick stupid. Why would you want a substantial part of your herd to not have been immunized, when you’re in a close-contact community?

And here’s the deal. I don’t think this is mean-spirited. I don’t think anybody’s standing at the gate, gleefully cackling “No Pfizer for YOU, dearie!!!” I think this is just the kind of thing that happens when a class of people have become invisible. Have become non-people.

This is the kind of thing that happens when we crow about having “a sense of community,” and then forget to actually think about who’s part of our community.

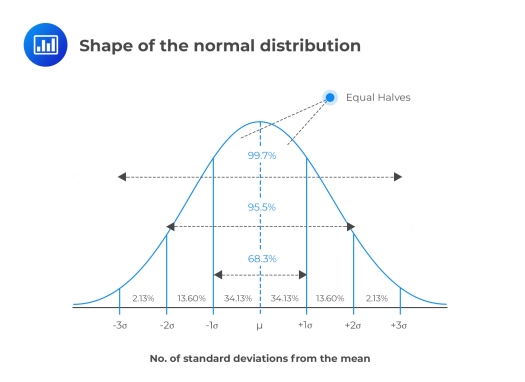

Lots of folks get upset at the idea of structural racism or structural sexism. They prefer to see a world of individual competitors who succeed or fail on the fair playing field of life. They insist that, because THEY THEMSELVES aren’t biased, that biases play and have played no role in their lives. They insist that, because THEY THEMSELVES aren’t biased, that bias plays no role in the lives of others

But my friend the adjunct has no way of competing for this vaccine on this campus, even as they have given years of service to this body of students. There is nothing that they could do, or could have ever done, to make them eligible for a benefit that others receive freely. There is absolutely nothing that is “their fault” about this decision made outside their control and without their consideration.

If a real estate agent shows people of color houses in only one part of town (knowing that they won’t “fit in” elsewhere), then that family will buy a house that won’t appreciate as rapidly, in a neighborhood that won’t be served by great schools, and won’t leave as much wealth for the kids to inherit. This used to be part of Federal housing and lending policy—now it’s cultural, a sense of who belongs and who doesn’t, cultural norms that add up over millions and millions of iterations into something stable and stubborn and enduring. Did those kids choose to be born six steps behind on the wealth stair? Of course not, just as George W. (“Daddy got me into Yale”) Bush or Mitt (“Daddy bought me a house in Boston while I was doing my MBA”) Romney didn’t choose to be born at the very pinnacle of that staircase. But it’s intellectually dishonest to not acknowledge those starting points, and the larger cumulative weight of history that they represent.

I was raised in a working class family, came from no economic privilege. But I can name you half a dozen times that I did some dumb thing as a teenager or young adult that, because I was white, got me a stern talking-to by a cop. If I’d been Black or Mexican American, each one of those would have been far more likely to have gotten me arrested. Or left me dead. It was bad enough being a long-haired hippie with a backpack in Amarillo, Texas in 1979… if I’d been a person of color, it would have been over.

We’re good at seeing individual cases and really, really bad at seeing patterns. And we’re absolutely terrible at seeing patterns we don’t want to see. So: was Eric Garner breaking the law by selling individual cigarettes on the sidewalk for a dollar? Sure, absolutely he was. Is my white neighbor breaking the law by having fifty leaking, dead cars scattered across his property, leaching motor oil and fuel and antifreeze and lead from the batteries into the soil above the river? Absolutely he is. So which one’s dead?

See, that’s what we mean by structural. It’s just another way of saying “patterns.” Patterns that maybe we should look at more closely.

When I accepted the challenge to write The Adjunct Underclass, I was clear from the start with my editor that I didn’t want to write another “combat narrative” of evil administrators and beleaguered teachers. I believed then, and believe even more strongly now, that what we’re seeing is an ecological collapse in which the species of college teachers is dying off. A combination of demographics and state funding and co-curricular services and educational technology and transfer credits and the broad cultural abandonment of workers have all contributed their tiny component to a structural discrimination in which someone who’s dedicated years of service to their students isn’t deemed a “real person” for purposes of public health.

But we see simple cause-and-effect more easily than we see systems. We see individual cases more easily than we see patterns. And we see, and accept, what is more easily than we imagine what might be instead.